Why Shoot Film in the Digital Age?

Why Shoot Film in the Digital Age?

I’m a cinematographer by profession and I think it’s the best job in the world. Like many in the media industry though, I like to spend my spare time exploring creative outlets outside work. I can’t draw or paint, I was never a great musician, and I can’t be bothered with poetry, but stills photography works for me.

I’ve been fascinated by it since I was a child and it’s what led me to the job I do now. It allows me the the space to be creative on my own terms and to work to my own schedule, without deadlines or editorial strictures. I photograph friends and family, wildlife, landscapes, still life, broken buildings, abstracts, pretty much anything. Sometimes it’s just the odd happy snap and sometimes it’s larger projects that are a bit more serious and thoughtful.

So, given the obvious and innumerable benefits of digital cameras, why are some people, myself included, still messing around with old metal boxes full of cogs, springs and strips of celluloid? What makes us want to spend hours in a darkroom, up to our fingertips in smelly liquids, doggedly pursuing the unattainable, and swearing to ourselves? Well, I’ve processed the question, and developed some ideas and framed my thoughts.

A large format camera up a hill, waiting for the rain to stop. Peak analogue.

Film Cameras Are Cool and Cheap

The mass move to digital means that values for film cameras have crashed in recent years. That’s great, because many good quality bodies, lenses and accessories can be easily sourced on the eBay and what have you, for a fraction of their original cost. A hundred quid or less can get you a used but professional quality 35mm or medium format camera that might have cost thousands when new. There’s always the genuine possibility of picking up something fantastic for a tenner at a car boot sale too. Most of these things have pretty much fully depreciated, so if you don’t get on with them, you can usually sell them on at no huge loss, or even a profit.

There’s also a growing market in plastic and toy cameras, pinhole cameras, instant cameras and all sorts, many of which are quite cheap and can be bought new.

This is an early Linhof Technika from 1947. I bought it from a guy I met in Arizona for $200, and it works perfectly.

I like nice cameras but I’ve never been one to fetishise the tools of the trade in the way that some people like to do. When I look at images people post in various film user groups, I see a lot of pictures of olden-days looking cameras, artfully placed next to some rolls of film and a cup of posh coffee, or slung over the back of a chair in a shaft of sunlight. I’m not sure what that’s all about. Perhaps it’s some inspirational, hipster lifestyle thing. Personally, I can’t be much arsed with all that, but if you want to accessorise with cool, shiny, retro cameras, there are plenty of options.

Having said that, there’s definitely something very satisfying about using really-well built, fully-mechanical tool that’s been beautifully engineered to do a specific job. I’m as guilty as the next person of enjoying the understated, whispered click of a Leica cloth shutter, or the precision feel of a silky-smooth, perfectly-damped manual focus lens action. Mmmmm. Oooooh.

Ahem... anyway, despite recent advances in electronics and engineering, I find those more visceral pleasures are often absent in modern digital kit.

It’s Pretty Simple

I think there’s a perception that using film is really difficult and technical. You can make it like that if you want (and many do), but it doesn’t have to be that way.

Taking analogue photos is all about putting some light-sensitive material in a dark box, and exposing it to light through a hole. That’s it, really. Anyone holding this remarkable piece of knowledge has all they need to start making creative and rewarding images. You can let the camera take care of all the settings, or you can go into great depths of technical geekery. I do both, and everything in between.

Processing the film is similarly as straightforward or as complicated as you want it to be. For greatest simplicity, you can send your film off to a lab for developing, and they’ll send you back the slides or negatives, and some quick prints or scans to look at. You’ll feel the joy using of film immediately, but lose some of the control that it can offer. If you’re a massive keener like me, you can develop and print in the darkroom, using traditional or alternative processes, and have control over all the technical and creative parameters. There are many points in between, so you can explore those and find the process that best suits you.

A Rolleiflex medium format camera. Not particularly cheap, if I'm honest, but very simple and lovely to use.

It’s a Great Way to Learn About Photography

It’s easy for people of my age to forget that there are is a generation of young people in movies and still photography nowadays, who have never set eyes on a piece of film. Many universities and colleges only teach digital, even on degree courses, since the students go on to work in professions that mostly abandoned film ten years ago or more.

As a young man, I learned the hard way about how to get the results I wanted. I did that on film because that’s all there was in the mid 1980s.

A good example was learning about exposures. I was a bit over-ambitious technically, and was always attempting complicated, extreme macro work with extension tubes and flash guns, all of which required a bit of arithmetic. I made things even harder for myself by using slide film, which can be incredibly sensitive to incorrect exposures. I would spend hours taking the photos of tiny bugs, in the hope and expectation of achieving some technical tour-de-force. I would wait for days for that box of beautiful Kodachromes to come back from the lab, only to experience yet again the sinking disappointment of finding most of them to be horribly under- or over-exposed. Once I got over the terrible injustice of it all, I wanted to know what went wrong, so sat down and learned more about f-stops, flash guide numbers, and equations for exposure compensation, magnification ratios and all that.

Now, I’m not suggesting we should all be doing this, but the point is that using film does allow us the space to make mistakes. It’s a while before we see the results. The lessons are often learned later and harder, but that’s what makes them hard to forget. We can’t always go back and fix problems, but we can learn for next time.

If digital had been available in those days, I would have had the instant feedback on exposures, enabling me to make adjustments as I went along. I wouldn’t necessarily have understood why I was making those adjustments, or bothered to learn how to calculate them. I would have just left the camera on Auto or ‘Running Man’, or kept going up or down with the exposures, checking the histogram until it gave me the right answer. I would probably have achieved better results much faster, but useful as they are, I never learned a bloody thing from a histogram.

I like the not knowing, and that’s the thing with film: you never really know what’s on it until you process it. You can try to pre-visualise, to pursue a certain look or effect, to imagine how it will look, but you don’t know for sure. It allows for serendipity, for making mistakes, for happy accidents. In fact, I like unhappy accidents too. I learn from them, and apply what I’ve learned the next time I’m taking a photo.

Image Quality

We have come to view most images on our 8-bit screens, quite small and over-sharpened to compensate for the failings in the display and inter-webular distribution technology. We don’t see many analogue prints any more, so when we do come across them, we are struck by their depth and clarity. I wish I could show you what I mean, but I can’t because you’re looking at a screen that can show only a limited range of colours and tones. I’d have to show you the print in real life.

Large format film is great for capturing high levels of detail in the landscape, just ask Ansel Adams. Not that you'll see much of it here!

Since the dawn of digital, there has raged a frankly tiresome debate over whether digital or analogue offers better quality. In the end, it comes down to which parameters you use to measure ‘quality’, and how much you value them. Digital is used for a multitude of practical reasons beyond the aesthetic or technical. It’s well-established in all our lives and it’s never going away, so the discussion is sort of irrelevant. Analogue and digital are just different ways of working.

However, I don’t want to dismiss the argument entirely, as the issue of quality is often raised. Also, I just want to challenge the base assumption that many people have, that digital is newer and therefore always ‘better’…

Let’s say we were to try to compare in a scientific way the quality of the output from a digital, with that from a film camera. To assess the ‘quality’ we would have to break it down into measurable technical parameters, such as sharpness, resolution, noise/grain, colour depth, sensitivity, dynamic range etc.

We could easily find a way to show that the digital output is superior to film in all those parameters. Conversely, by choosing the right lens, film stock, test image, processing and viewing conditions etc, we could prove categorically that film is better in every measurable way. There are so many potential variables that could alter the result, that any conclusion reached would have so many caveats attached, as to be effectively meaningless.

Where it starts to get a bit more interesting is when you shoot on larger formats. If you go to medium format film (usually defined as 6x4.5cm, 6x6cm, 6x7cm, basically anything that’s 6cm in at least one aspect), you have to enlarge the image less to make the same size of print. The benefits of the larger image area include improvements in all of our technical parameters, mainly sharpness, resolution, and grain (but also dynamic range) so it gets harder for a DSLR to compete. There is also a different aesthetic, because depth of field at equivalent lens angles is different. There are other provisos, but in effect it means that for a relatively small amount of money you can get a used medium format film camera, which has the potential to put any DSLR to shame in the quality stakes.

This effect is even greater if you use large format film, generally defined as 5x4 inches or bigger. The image area on 5”x4” is over 13 times that of a full-size DSLR sensor. Again, the aesthetic is different and there are other technical considerations, but a large, good quality print from a large format negative has the ability to draw you into the picture, in a way that a digital image can't often do. You can look as closely as you like and you just see more and more spectacular detail, with no visible grain. The best news is that a large format camera needn’t be expensive either. Just a couple of hundred quid can give you access to this incredible level of detail and resolution.

Of course, I’m not saying that the pursuit of resolution or other specific parameters is what talking photos is all about. Obviously it isn’t. I’m just saying that although digital can do all the technical stuff really well, film still has the potential to do it much better.

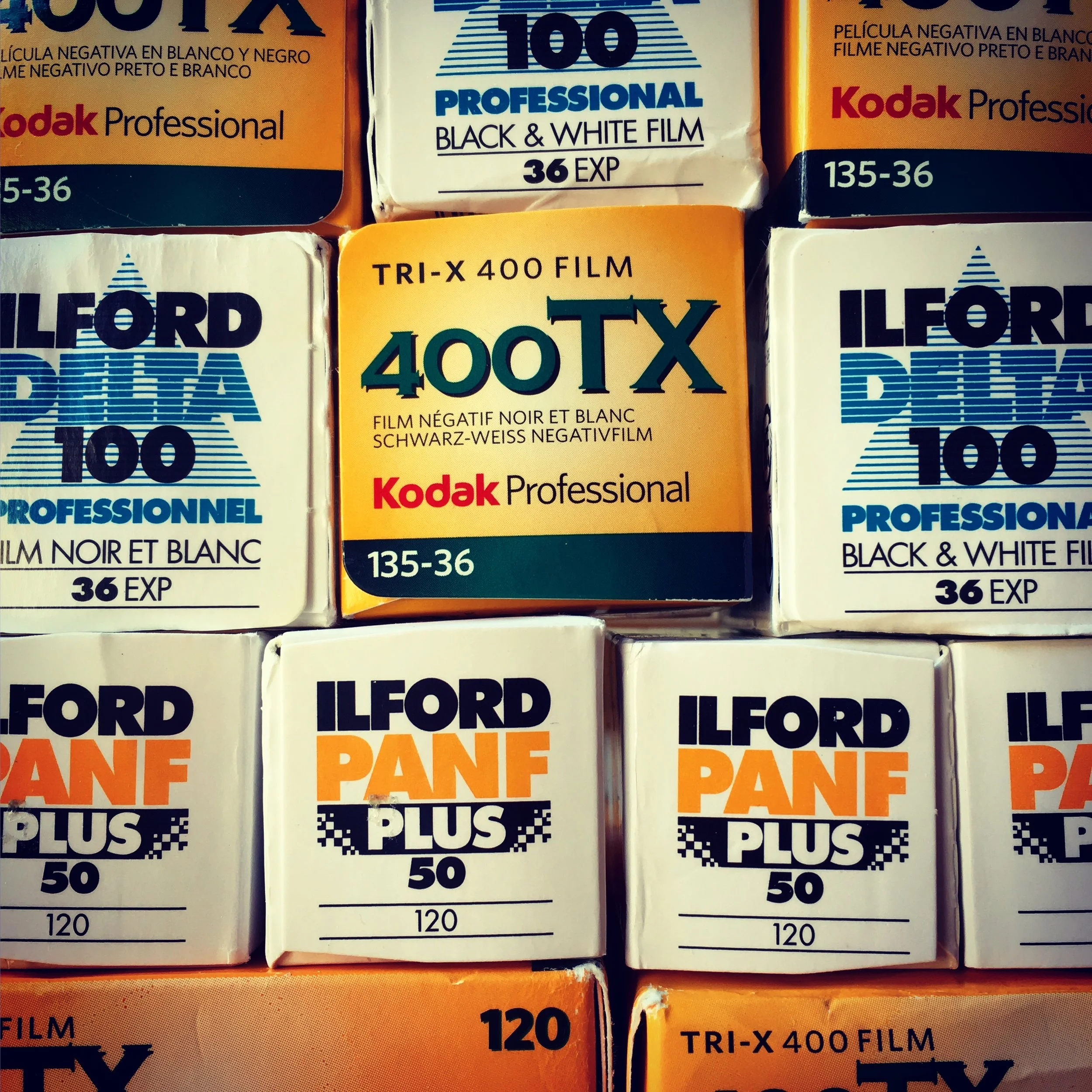

Some of the stuff that routinely takes up space in my fridge.

Choice of Materials

There isn’t quite the range of film materials that there was in the pre-digital age, but you can still buy lots of different types, in a number of different formats. There is colour slide, colour print, black and white print, high speed, low speed, infra-red, X-ray and even instant film. You can get all different sizes from rolls of 110, 135, 120, and sheets from 5”x4” to huge formats. They all have different characteristics, some have accurate flesh tones, some have pastel colours, some are punchy, sone are grainy, some are sharp, some can be pushed beyond their nominal box speeds and some are just weird.

It’s a similar story with the processing materials. You can still get it done by post or on the high street, but if you prefer to do it yourself, you can still buy a good variety of chemicals and paper. Most of the mainstream stuff is still there, and if you get really stuck you can make them yourself.

Despite the loss of many analogue products over the years, a recent resurgence of interest in traditional processes has resulted in new products being developed and even old ones being reintroduced as companies have restructured.

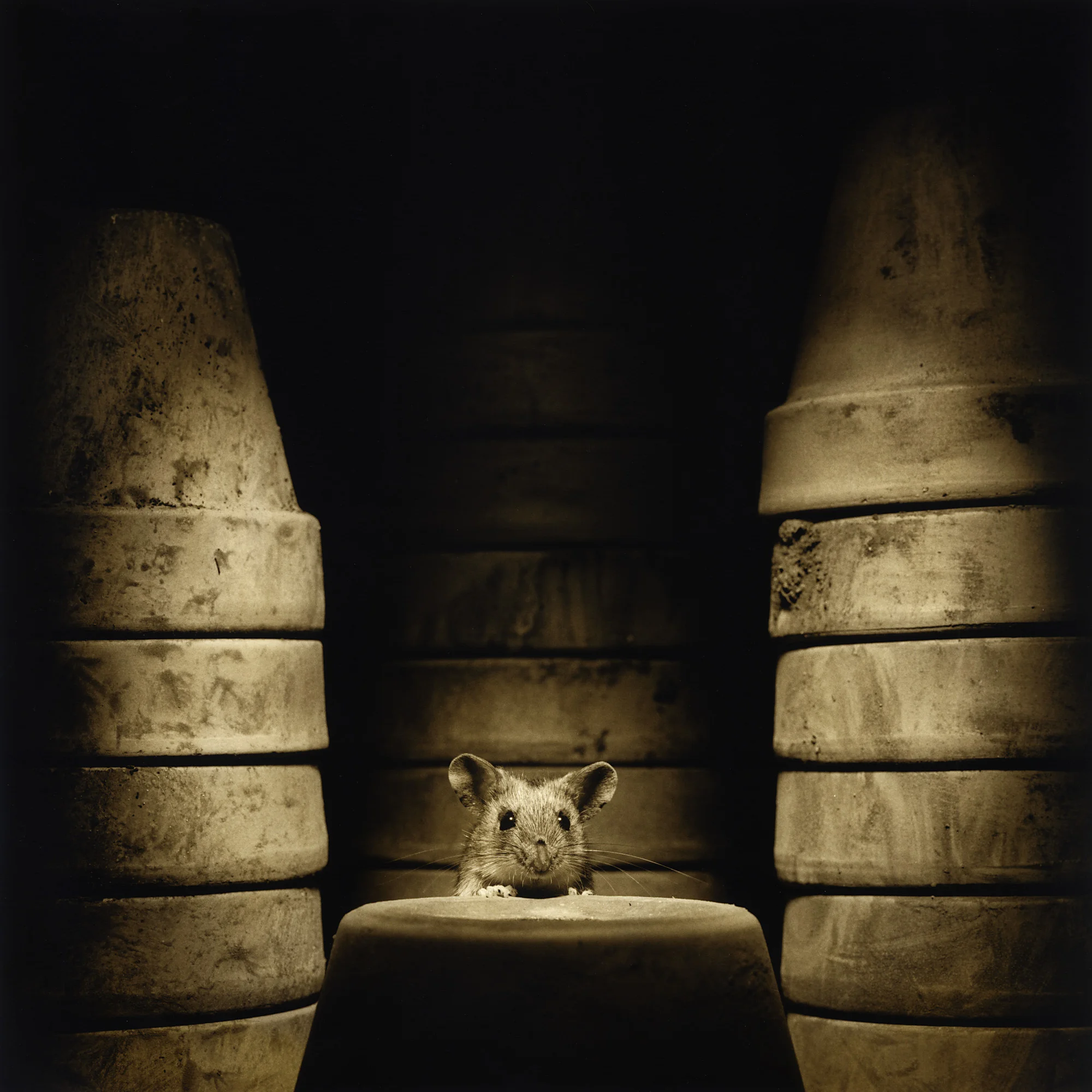

A wood mouse in my garage, taken on my old Hasselblad. The materials used include Ilford Delta 100 film in medium format, Ilford Multigrade Warmtone Fibre-based paper, Ilford chemicals, Fotospeed Sepia toner and a mouse, all of which are readily available.

It Slows You Down

Shooting on film sometimes forces us to use cameras are heavier and more cumbersome than with digital, especially if it’s medium or large format. The time and effort it takes to get the camera set up and in place generally increases with film size. If the camera is not automated you might need extra time to do your light metering and adjust your focus and exposure settings.

The other thing that increases with the size of the film is the cost of the film and processing for each shot. If I use a 35mm camera, the cost of exposing and developing a frame might be a few pence, but for 5”x4” it can be several quid, and that’s before any printing or scanning.

This might all sound like a disadvantage when compared to digital, where you can just pull the camera out of the bag and rattle off thousands of frames at no particular cost. For me it doesn’t seem to work that way.

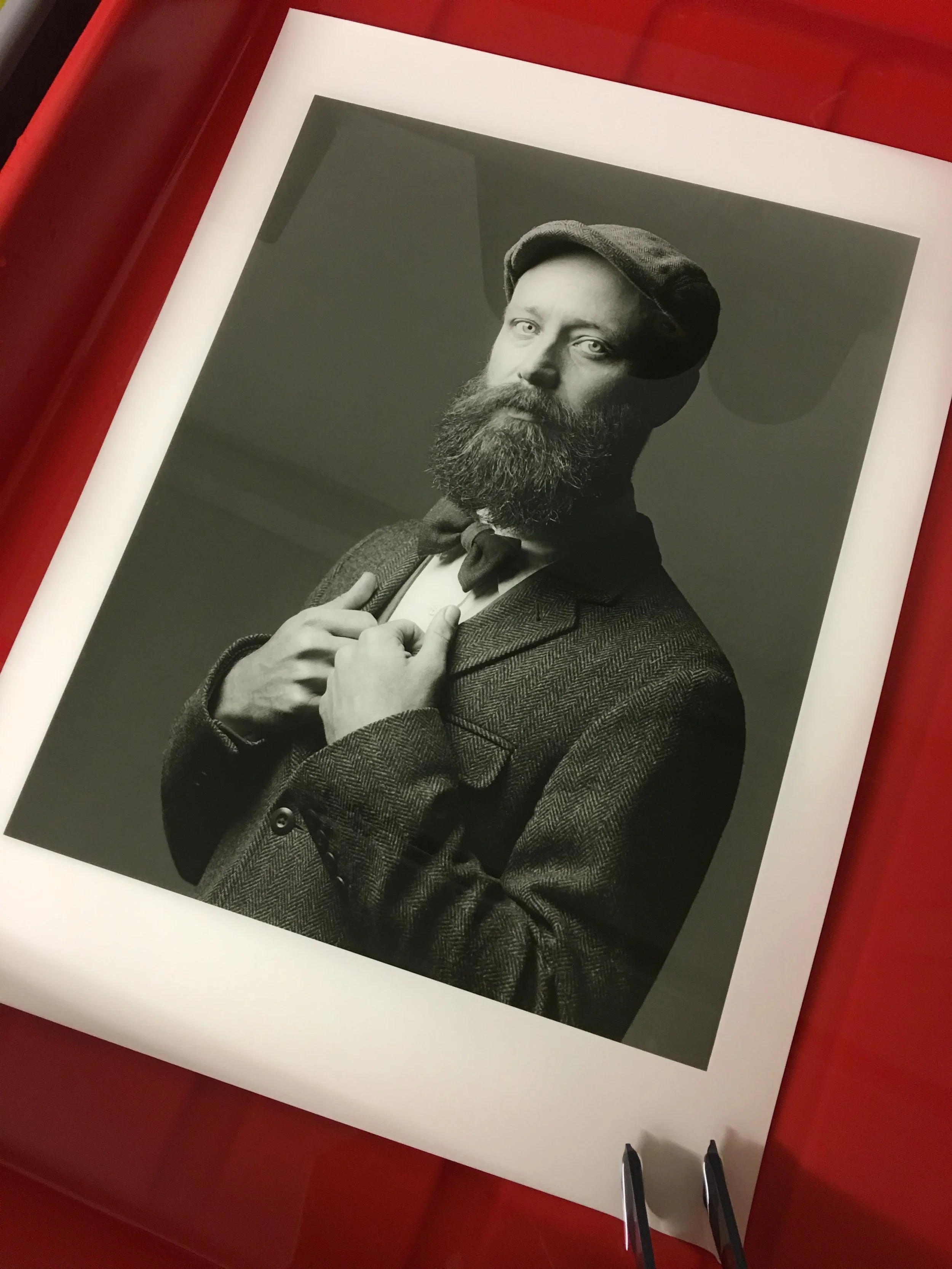

The best example for this is my portrait photography, where I’m usually only looking for one good shot. If I were shooting digital it would be tempting to take hundreds or thousands of frames in the hope of finding the perfect shot ‘in there somewhere’, but that shot is never there. Shooting large format film means a heavy, bulky camera, which needs to be on a tripod, is fiddly to load and takes some effort to set up. All of it slows me down. The knowledge that each exposure is going to cost me £5 certainly concentrates the mind too. It makes me ask myself if the lighting is as good as I can make it, whether my framing is right, and if I have really nailed the focus. Every time I don’t take a shot because the answer to one of these is ‘no’, I save myself five quid. When the answer is yes, I take the picture and consider it a fiver well spent. In either case, I have only taken a picture I want, and I’ve wasted no frames.

My good friend, Ian. This shot took the best part of a day to set up and light, but we only exposed a couple of sheets of film.

It’s a Shortcut to Greatness (almost)

When I look at the images that I aspire to, by the photographers who influence me, I find that most of them were shot on film, and in black and white. Of course there are incredible photographers working digitally too, it’s just that it’s the analogue era that I’m particularly drawn to. In some cases these images could equally well have been shot on digital, and I dare say that had that technology been available at the time, they might have used it, but the fact remains that they were shot on film and they are what they are, at least in part, because of it. The analogue process always had its limitations and imperfections and these inform the way it looks.

Yes, I know that some of these filmic characteristics can be reproduced digitally. There are film-type software effects that ape the appearance of certain film characteristics, camera faults, light leaks etc. They’re quite good though, and I use them all the time on my phone, but not because I think they’re particularly convincing as film looks. They just make my otherwise lacklustre images a bit more eye-catching.

The analogue image has some of these characteristics built in. You don’t have to use filters and sliders, you just have to choose the film and camera with the characteristics you want, and do the process to achieve the look you’re after. Some effects, like grain, saturation, colour skews etc. are highly predictable. Light leaks, flares and scratches are a bit less so.

Most of us, when pursuing any creative endeavour, will draw inspiration and influence from what has gone before, or to put it another way, we ape our heroes. An easy way to do this is to copy their technique. When you’re lazy like me, you look for short cuts. So, if I wake up in the morning in an Henri Cartier-Bresson frame of mind, with the idea of doing some reportage-style photos that have the technical aesthetic of Kodak Tri-X shot on a 35mm camera, the best possible route to this is to shoot Kodak Tri-X on a 35mm camera. It still gives options in processing and printing, but it takes out so many variables that I have neither the time nor the need to explore. It will be what it will be, and it won’t turn me into Cartier-Bresson, but it will point me in the right direction, and when all the right elements of the picture are in place, it will look bloody great.

A classic look from 35mm black and white film. I was trying (and failing somewhat) to ape the genius of one of my favourite photographers, Elliott Erwitt.

You Don’t Need a Computer

Of course there are highly sophisticated processing options available to the digital worker, including some very convincing filters that replicate specific film types. Often, even committed film users will scan their negatives and do all their processing in the digital domain. It’s a perfectly valid and practical solution, which some feel gives them the best of both worlds. People have done incredible work that way, but personally I would feel I was losing something of the fun and creativity that making analogue prints in the darkroom can offer.

The fact that I would have an infinite number of digital processing options open to me for determining the look a photo has never made me take better pictures. I don’t have endless time to go through the filters and sliders, and I don’t want to sit in front of a computer getting eye strain and haemorrhoids any more than I already do. After all, the point of stills photography for me is to get away from all that. Keeping it analogue means never having to sample anything, never having to settle for a limited colour palette or tonal range, never having to deal with banding or compression artefacts. I can be free from the myriad tyrannies of pixel counts, bit depths and printer profiling.

Printing in the darkroom offers plenty of creative choices. While it can be time-consuming and frustrating, I’ve never felt constrained by it. You can fiddle and fine-tune to a very high degree, and there is huge pleasure and satisfaction in making an analogue print that you’re really happy with.

Not everyone has the space to build a permanent darkroom, but there are other options. many major towns and cities have fully-equipped darkroom facilities that can be hired, and most of those will offer help and instruction on how to use them. Lots of people will temporarily convert a part of their living space for a day at a time. You just need some blackout material to stop daylight getting in, a steady supply of running water, and some sort of work surface. A small kitchen is ideal.

The Print

Now, I like a nice analogue print. For me it’s the biggest single reason for shooting on film. It is the culmination of my endeavours. We treat prints differently to a digital file. We put them in albums, we frame them, hang them on our walls to decorate and improve our living spaces. We print the images that mean most to us, that we want to see every day, or that we want others to see. They are tangible, tactile objects which can excite all our senses. We keep them for years and pass them down through generations.

Of course, you can make excellent prints from digital images, and you can make as many as you like and they will all be identical. That’s fine, there is merit to consistency, but to my mind, that is to reduce the print to merely a medium which carries an image.

A print being made in the darkroom.

An analogue print is a special thing. You can’t email it or put it on Facebook or Instagram and retain much more than a ghost of the original. You can see what it’s a picture of, but you don’t get any real sense of the print itself.

To make an analogue print in the darkroom is to make an entirely fresh piece of work. It takes time and skill to do it well. It is an organic thing, which has been worked by hand, like a sculpture or a painting. You can achieve remarkable consistency in making multiple prints, but the process is organic and dynamic. Batches of paper and chemicals have slight variation in manufacturing and age, the colour of the lights in the enlarger change, the developers and toners gradually exhaust with time and use. You can’t usually tell them apart but there are never two analogue prints exactly the same, though a good darkroom printer will ensure that they are consistent to a very high degree. For me, this means the analogue print is an individually crafted object, not endlessly re-produceable at the strike of a Return key, but a thing of beauty and value in its own right.

The idea is straightforward enough. You put your negative in the enlarger, which projects the image onto a piece of paper. The paper goes through the developing process, and the image is permanently fixed. Then you hang it up to dry and you have a beautiful analogue image that will last a lifetime or more. You use what you know and the tools at your disposal to interpret the image, to make the print, which is the final embodiment of your vision. It’s where you take the elements you have captured on the celluloid film, deciding which bits to keep, which bits to lose, which to lighten and which to darken. A beginner can do it and make a great print, and an experienced printer can make terrible errors. The thing is it’s addictive. You learn to dodge and burn, you begin to understand paper grades, you refine and improve your technique, you learn from your mistakes. You want to do another and another, to get really creative with developers, bleach and toners. It can be hugely satisfying and rewarding or deeply frustrating and unfulfilling. It’s pretty much always bloody expensive but it’s definitely worth it!

This final print has been thio toned to give the sepia colour. It also makes the image truly archival, so Kieran's beard can be marvelled at for centuries to come.

The Ruddy Joy of It

I remember well the first time I made a print in a darkroom.

I was shown the basics by a supply art teacher at school, and he left me to it. It was a picture of a dry stone wall I had taken near my house. It wasn’t the best photo I have ever taken, but I was totally amazed by the sight of an image forming on the paper, slopping around in some liquid under the red light. I saw shape and texture in the stones, light and shadow, tiny details of moss and lichen. I found this hugely exciting and went to show my art teacher as soon as the print was dry. It was after school and he was sitting having a cup of coffee with another teacher. They were both polite but definitely not as overwhelmed by this miracle as I thought they should be. No matter, I was blown away by my first sight of the image forming, and I still get the same feeling when I’m hunched over the dev tray in my own darkroom.

It also got me thinking about how what an incredibly clever invention a piece of film is. It’s wondrous to me that you can capture so much detail, so much information, in the space of a tiny fraction of a second, and that it this now a record of that moment, which could potentially last for ever. It made me engage with some old family photos that were lying around at home. Transparencies and prints, showing people as children who were now either grown up or long dead, sitting in cars long scrapped, or playing in streets long demolished. The idea that some of the photons which had bounced off those people were recorded on a piece of film, in the blink of an eye, and I was now able to hold these things in my hand, I found almost overwhelming. It gave me a sense of connection with the past and to my relatives, which as a teenager I had thus far probably been lacking. It also made me very much more aware of the directionality of time, and the fact that it’s a one-way street. That idea of entropy and descent into chaos has since informed a lot of my work.

Here's some of that entropy happening in Pripyat, near Chernobyl.

It Lasts Forever, Almost

Analogue images, if fixed, toned and stored correctly have an indefinite lifespan. There are plenty of images in archives today that are as good when they were taken nearly 200 years ago, at the dawn of photography. I’m not saying we’re all going to be making important historical documents of great value to the nation, but they might be important to somebody. The idea that the physical images we make have the potential to outlive us and several generations of our descendants is an appealing one.

Great claims are made for the longevity of modern inkjet dyes but the truth is that nobody knows. Silver salts are incredibly stable and are resistant to fading. If people are buying photography as art, either as an investment, or to hang on their walls, they want to know for sure that it won’t fade or discolour over time. Archival printing is relatively easy with analogue materials and it’s a proven way to ensure that the images will last many lifetimes.

Somewhere in my mother’s house, there’s an old album, and in there is a blurry picture of me running around naked with the garden hose in the summer of 1976. It was taken by my mother, on a Kodak Instamatic. There is an envelope next to it, with the negative inside, which contains a direct record of the light that bounced off me when I was 3 years old. Nothing I’ve taken on my phone can beat that.

I wonder if our descendants will look at our Instagram feeds in years to come and feel that same sense of connection with the past. Maybe they’ll look at the eminently disposable pictures of the avocado on toast we had for breakfast yesterday and decide it’s just too much information and they don’t much care.

This is a picture of my baby niece, Ivy, taken a couple of years ago. My sister has a print of it which, assuming it's not mouldering away in a damp basement somewhere, she will be able to gaze upon for many years, long after she has lost her phone or forgotten her Instagram password.

In conclusion, I’d like to leave you with a quote on the subject of film vs digital. It is attributed by many academics to the great Victorian pioneer of creative portrait photography, Julia Margaret Cameron. It is as true now as it was in her day:

‘Two weeks in the darkroom can save ten minutes in Photoshop’

WS